XLM Insight | Stellar Lumens News, Price Trends & Guides

XLM Insight | Stellar Lumens News, Price Trends & Guides

Every year, typically in the fall, the Internal Revenue Service performs a quiet but critical piece of system maintenance. With little fanfare, it releases its inflation-adjusted figures for the upcoming tax year. This year, the IRS announces new federal income tax brackets for 2026, and as expected, the changes are being framed as a form of relief for taxpayers.

But let’s be precise. This isn't relief in the way a tax cut is relief. This is the system preventing its own absurdity.

Think of it like a treadmill. Inflation is the machine’s speed, and your income is your running pace. If the treadmill speeds up (inflation rises) but you don't run faster (get a raise), you fall off. But if you get a cost-of-living raise that merely matches the new speed, you're running harder just to stay in the same place. "Bracket creep" is when the tax code acts like a faulty treadmill that doesn't account for the increased speed, effectively punishing you for keeping up. The annual IRS adjustments are simply the machine’s calibration, ensuring you aren't penalized for jogging in place. It’s a necessary function, not a generous gift.

The core of the 2026 adjustments lies in widening the income thresholds for each tax bracket. The numbers themselves are straightforward. For 2026, the standard deduction for married couples filing jointly will be $32,200. For heads of households, it’s $24,150, and for single filers, the figure is $16,100. These are modest increases designed to reflect the higher cost of living.

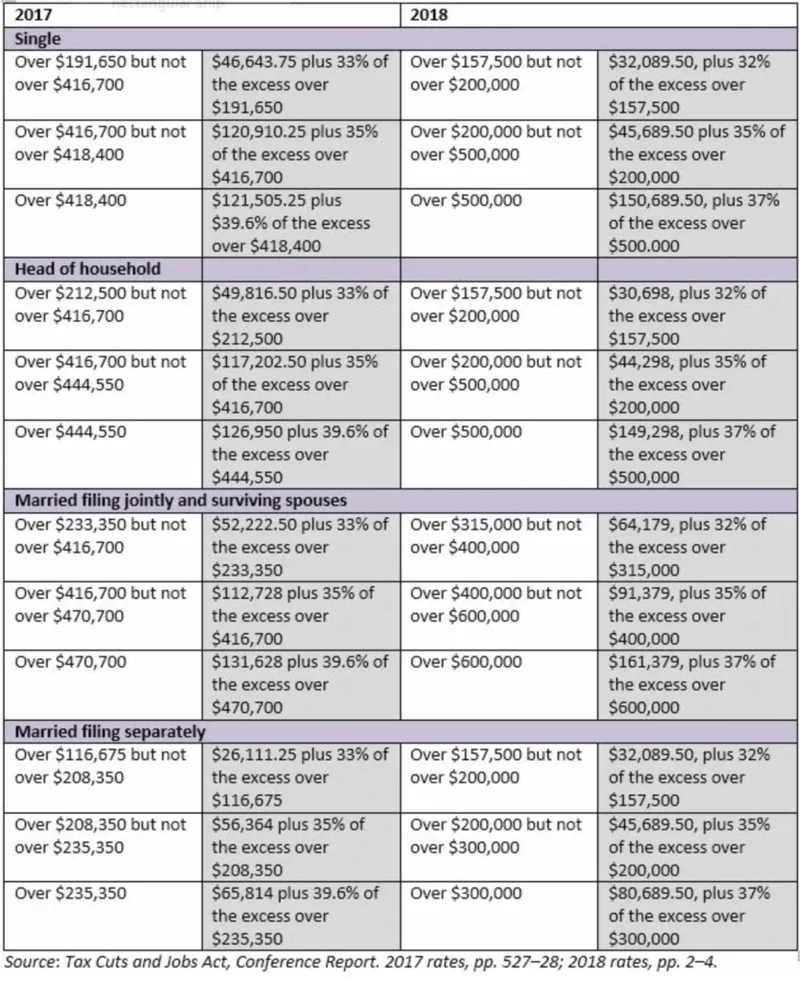

The more significant change is in the brackets themselves. The goal is to allow Americans to earn more before they are pushed into a higher marginal tax rate. The source material provides a somewhat simplified example: a single filer making $50,000 will find their income taxed at a top marginal rate of 12% in 2026, whereas in 2025, that same income level would have tipped them into the 22% bracket. This is the adjustment working as intended. A salary that was once on the cusp of a higher tax bracket is now nestled more comfortably in a lower one.

But this is also where I find the official narrative slightly misleading. I've analyzed countless regulatory releases, and the way these changes are presented often obscures the underlying pressure. The announcement feels less like a financial analysis and more like a PR maneuver designed to preempt criticism. Is a system that requires constant, reactive adjustments to prevent it from penalizing citizens for inflation truly an efficient one? Or is it a sign of a deeper disconnect between our tax structure and the economic reality faced by households?

The data also points to a very specific, and temporary, provision for seniors. A clause in the "One Big Beautiful Bill Act" provides a temporary tax deduction of up to $6,000 for individuals aged 65 and older. However, this provision is explicitly temporary (it’s set to expire at the end of 2028) and is means-tested, available only to single filers with an adjusted gross income of $75,000 or less. This feels less like a structural fix and more like a political patch. Why the expiration date? What is the long-term fiscal plan for seniors on fixed incomes when this temporary relief vanishes? The data doesn't provide an answer.

Context is everything. These adjustments were announced even as the IRS itself is navigating an agency-wide furlough due to a lapse in federal appropriations. The image is one of a vast, automated machine continuing to function while the humans who oversee it are sent home. A spokesperson was quick to note that the "lapse in appropriations does not change Federal Income Tax responsibilities." In other words, the system's demands on you are unwavering, even when its own internal operations are strained. Taxpayers with filing extensions must still meet their deadlines. The machine never stops.

This brings us to the core analytical question: Are these inflation adjustments, calculated using broad national indices, truly sufficient? The Consumer Price Index is a blunt instrument. It averages the cost of a wide basket of goods and services, but the real financial pain for most families comes from outliers—the costs that far outpace the average. Housing, healthcare, and higher education costs have, for years, grown at a rate that makes the headline inflation number look quaint. About 3%—or to be more exact, the 3.2% annual inflation rate seen recently—doesn't feel like 3.2% when your rent has jumped 15% and your health insurance premium is up 20%.

So while the IRS adjustment prevents your cost-of-living raise from being completely consumed by a higher tax bracket, it does little to address the fact that your actual cost of living may have outstripped that raise entirely. The calibration is mathematically correct based on its own inputs, but are the inputs themselves reflective of reality? It’s a crucial discrepancy. The system is designed to keep you from falling behind relative to the tax code, but it is not designed to help you get ahead in the real economy.

This is the central issue. We focus on the nominal dollar adjustments because they are tangible and easy to report. But the real story is the erosion of purchasing power that happens before taxes are ever even calculated. These bracket shifts are a response to the symptom, not the cause.

Ultimately, we must see these 2026 tax bracket changes for what they are: a technical necessity, not a policy victory. They are the financial equivalent of adjusting a clock for daylight saving time. You haven't gained an hour of time; you've simply adjusted your measurement to align with a new reality. To celebrate these changes as a "tax break" is to fundamentally misunderstand the economic forces at play. This isn't the government giving you a hand up; it's the government slightly loosening its grip as the current pulls you downstream. The real question we should be asking isn't how much the brackets shifted, but why they need to shift so significantly, year after year, just to maintain the status quo.